Let the one who has never loved be the first to pick up a stone (and then put it down, because throwing stones is dangerous). After all, love is one of the strongest, most ubiquitous and at the same time – because of its universality – the most difficult emotion to define. You can love your life partner, your family, your friends, your offspring, and even more: animals, plants and basically anything that comes to your mind. The ancient Greeks distinguished types of love, and we know them from Polish lessons or history: agápē, érōs, philía and storgē, i.e. altruistic love, passionate love, friendly love and parental love, respectively. And although from a philosophical and psychological points of view they are diametrically different, each type of love has a common core – a strong attachment – and, depending on its form, various other “add-ons”. Biologically, the chemical compounds, colloquially known as 'love molecules', usually have many different functions in the body. This is one of the reasons why we as a species are so susceptible to falling in love. Therefore, to lose one's entire head for the sake of only one pair of eyes is human. Head and all its contents, because who in a state of love has never done something utterly stupid? Probably only someone who has never been in love. In this article, we will try to prove that love is not only blind, but also a bit stupid (though the sense of smell is not bad either), and we will also suggest how to deal with it when it disappoints us.

"There are plenty of fish in the sea"? That is, on what basis we choose a partner

Now that we have established that Cupid's arrow can pierce almost any heart, we should consider an explanation – why is this the case? Why do we lose our minds, become obsessed and create scenarios for our lives together? The answer, as in biology, is complex. One could say that, from a scientific point of view, romantic love is a storm of hormones with a hailstorm of neurotransmitters in the evolutionary firmament. Indeed, it represents an adaptive mechanism that favours the choice of a suitable partner and the maintenance of a long-term relationship that guarantees the care of offspring. Evolutionarily, strong social bonds generally aid survival and, in particular, parental cooperation related to food acquisition and protection from predators increases the likelihood of offspring survival and gene transfer. However, the number of people in the world is approaching ten billion, while we have probably met hundreds of people in person – how do we select our perfect breadwinner or keeper of the home from among them? Well, you have to have a nose for choosing the right partner – literally, because one of the most important things in perceiving someone as attractive is pheromones, i.e. volatile chemical compounds that influence our hormone levels and emotional reactions. We subconsciously prefer the scents of people with different tissue compatibility genes, related to immunity and genetic diversity – this increases the chance that our eventual children will be healthy. And as we know, health is ok key importance, which is why we often intuitively perceive features associated with it as attractive – such as facial symmetry or healthy skin. And although culturally the heart is blamed for the ups and downs of love, this information is received and analysed by the brain outside our consciousness. It is there that, depending on many individual, social, biological and "spur of the moment" factors, all the reactions that ultimately condemn us to the sentence of falling in love take place.

Venus or Karenina? – or how women love

Socially, romantic love and the passion and turbulence associated with it are mostly attributed to women – after all, the most important deity of love is Aphrodite, not Alfred, and the most extreme and altruistic acts of love in culture involve women. However, do they actually love deeper, stronger and to the point of madness? It's impossible to measure, but researchers are currently leaning towards an interesting theory suggesting that romantic love evolved from a mother's love for her offspring – everyone probably has that one relationship in their life where the man constantly causes clothes to shrink in the wash and practically invents a new element while trying to cook dinner. Perhaps it is some derivative of the motherly instinct, telling her to take care of a helpless creature just learning to live, that prevents his partner from breaking up? Both maternal and romantic love share common neurobiological mechanisms related to the activation of the reward system in the brain in response to specific social behaviours. Both bonds are also characterised by a decrease in the activity of the brain structures responsible for negative emotions, anxiety, social judgement and judgement – perhaps we now recall how our friend, with a feeling close to ecstasy, described to us her Romeo, Prince Charming, Apollo and Andrzej Kmicic in one. However, when she finally showed their photo, an awkward silence was the least critical response we were able to give. It is the reduced activity of brain regions associated with critical thinking and the increased release of dopamine responsible for euphoria in the early stages of romantic love that causes us to overlook our partner's (often numerous) flaws and perceive their strengths as greater than they actually are. Furthermore, since the evolutionary purpose of romantic love is to increase reproductive success, sex hormones, including estradiol and progesterone, which are associated with feelings of sexual desire and partner attractiveness, also play an important role. Oxytocin, which was originally thought to be a hormone mainly associated with lactation and childbirth, is also involved. It is responsible for attachment and is released under, among other things, the influence of cuddling. Its levels are significantly higher in women, for example because of the increased production of it by sex hormones. And while it is crucial for attachment to one's partner and a sense of security, in certain situations it can exhibit paradoxical effects, such as increasing anxiety about the relationship. What about the madness? Oxytocin levels are elevated in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder, some of whose symptoms, such as obsessive thinking, are common to romantic love. So, if high levels of oxytocin are actually responsible for both obsession and love, it would explain all the tragic stories of women madly in love who were ready to sacrifice everything for the man they loved. We must therefore be careful not to end up sinking into madness like Anna Karenina by trying to fill our lives with passionate love like Venus.

Romeo or beast on testosterone? That is, how men fall in love and make love

We already know that one can go mad for love. And although women may be potentially more susceptible due to higher levels of oxytocin, this does not mean that men are not capable of such feelings (take Werter or Wokulski, for example). Also, contrary to popular belief, men did not come from Mars, and their feelings of love do not concern only the sphere of sex. On the contrary, research shows that men seek romantic relationships and are often the first to say “I love you”.

In addition, they are less likely to initiate break-ups and suffer more when the relationship ends. There are therefore many superstitions concerning the figure of the man in love, and its representation in literature is by no means merely a dramatic exaggeration. In the case of men, we are also dealing with a hormonal storm, in which an important component is – as in women – oxytocin, which causes an increase in loyalty, empathy, trust and attachment in relationships, and also increases the attractiveness of the partner. Vasopressin also acts together with oxytocin, which, especially in men, is responsible for mobilised behaviour, including the protection of the partner and family. It also ensures ongoing commitment and the feeling of satisfaction from a long-term relationship. Dopamine is also crucial for falling in love, of course, as it helps make love a pleasant experience by activating the reward system. When discussing hormones that affect male behaviour, testosterone cannot be overlooked. Men are often seen as ,'beasts on testosterone', but while higher testosterone levels are associated with pairing off and attracting sexual partners, it is not correlated with relationship longevity and romantic attachment. Therefore, men in satisfying relationships have testosterone levels that are approximately 21% lower than those in single relationships, suggesting the role of reduced testosterone in relationship commitment and fidelity to a partner.

Love addiction – the dopaminergic reward system

There are times when we get silly and crazy in love, but we can also get addicted to it. This is because, especially in the initial stages of falling in love, due to the high level of excitement and stress associated with the new feeling, we can behave as if we are in rehab. When our object of affection doesn't write back quickly enough (i.e. immediately), we tend to get nervous and, in lighter cases, check our phone every now and then and wonder why they have lost interest in us. We await a single message like a drug addict thinking only of taking another dose. And the moment we receive it, all withdrawal symptoms disappear and the brain basks in the euphoria that "They love us after all", regardless of how dry and unimaginative the response received after sixteen hours might be. This is just one of a palette of behaviours that put the colours of addiction on romantic love. Brain structures that are a part of the reward system, which plays a key role in the mechanisms of falling in love and attachment, are the source of this meandering madness. These regions include the ventral tegmental area, the nucleus accumbens and the caudate nucleus, which gained notoriety in neuroscience much earlier as areas associated with addiction. In addition, the fuel that drives the reward system is the familiar dopamine, whose levels are increased by both falling in love and taking psychoactive substances. "That touch acted like a drug," we sometimes hear in songs, and there is something to it – some scientists suggest that an overlap in the processes by which dopamine is released, the so-called dopaminergic overlap, potentially explains why experiencing love can resemble a feeling similar to taking cocaine or heroin. However, the role of dopamine goes far beyond addiction and love. It is linked to a wide range of other processes related to reward learning – including eating, drinking or having sexual intercourse.

Myocardial fracture – why does the separation hurt?

From a logical point of view, "broken heart" is of course a metaphor – the heart is a muscle and these structures do not, as a rule, suffer this kind of injury, more like contusions or tears. Furthermore, both the positive emotions associated with falling in love and the negative ones accompanying a break-up are processed in the brain, not in the heart. Yet it is what hurts us, and the term “broken” may not actually be that dramatic. It appears that the emotional stress of rejection initiates a similar brain response to that generated in response to physical pain. In addition to feelings of loneliness and increased emotional sensitivity, there are elevated levels of cortisol – the stress hormone – causing feelings of fatigue and discomfort and, in the long term, producing a range of physiological symptoms, including insomnia, headaches and increased muscle tension. No matter how you look at it, we lose a loved one as a result of a break-up, so the accompanying anger, sadness and racing thoughts are comparable to the feeling of mourning the death of a loved one. In some cases, more serious health effects can occur, including immunosuppression, endocrine dysfunction and broken heart syndrome (Takotsubo). The latter, also known as stress cardiomyopathy, manifests itself with poignant pain in and around the heart and even acute heart failure similar to a heart attack, but with a greater possibility of complete recovery. So how do you help someone who finds themselves in such misery? Above all, support for a person after a break-up should be personalised and only works if the subject of our actions perceives them as helpful. We are all different – some people need to be listened to, some need words of support and motivation, some need to go out together for distraction.. It is important not to push and do more harm than good by giving unsolicited advice or comments on how we think someone should act, as this can only make someone's psychological situation worse. In short, listen with understanding and take action on that basis. And what coping mechanism to take when it is our heart that is brought to tears? Above all, it is important to try to understand your emotions and not run away from the problem. Additional damage will be done by blaming ourselves or pretending that the situation did not happen. We should try to make up for the chemical deficiencies that the break-up has left in our brains – keep in touch with relatives and friends, take up physical activity or develop passions. In doing so, we will ensure that the necessary levels of oxytocin and dopamine are restored, the deficiency of which, after a break-up, makes our brains despair and our hearts break.

Two new competitions!

We will announce not one, but two competitions in which you will be able to test your skills in popularising science in 2026.

- Firstly: the second edition of the Competition for the best popular science text – in the same formula, with two categories (individual and team) and a limit of 14 thousand characters. One important novelty: we are increasing the prize pool for first place!

- Secondly: Popular science film competition, intended for student science clubs of the University of Lodz. It will provide the opportunity to win funding for the development of the club's activities.

The competitions start in January 2026.

Bibliogrphy

Ackerman, J. M., Griskevicius, V., & Li, N. P. (2011). Let’s get serious: Communicating commitment in romantic relationships. Journal of personality and social psychology, 100(6), 1079–1094.

Aron, A., Fisher, H., Mashek, D. J., Strong, G., Li, H., & Brown, L. L. (2005). Reward, motivation, and emotion systems associated with early-stage intense romantic love. Journal of neurophysiology, 94(1), 327–337.

Babková Durdiaková, J., Celec, P., Koborová, I., Sedláčková, T., Minárik, G., & Ostatníková, D. (2017). How do we love? Romantic love style in men is related to lower testosterone levels. Physiological research, 66(4), 695–703.

Babková, J., & Repiská, G. (2025). The Molecular Basis of Love. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(4), 1533.

Bartels, A., & Zeki, S. (2004). The neural correlates of maternal and romantic love. NeuroImage, 21(3), 1155–1166.

Bloodgood, M. (2016). Why do Breakups “Hurt?”.

Blumenthal, S. A., & Young, L. J. (2023). The Neurobiology of Love and Pair Bonding from Human and Animal Perspectives. Biology, 12(6), 844.

Bode, A. (2023). Romantic love evolved by co-opting mother-infant bonding. Frontiers in psychology, 14, 1176067.

Burnham, T. C., Chapman, J. F., Gray, P. B., McIntyre, M. H., Lipson, S. F., & Ellison, P. T. (2003). Men in committed, romantic relationships have lower testosterone. Hormones and behavior, 44(2), 119–122.

Cancian, F. M. (1986). The feminization of love. Signs, 11(4), 692–709.

Carter, C. S. (2017). The Oxytocin-Vasopressin Pathway in the Context of Love and Fear. Frontiers in endocrinology, 8, 356.

Carter, C. S. (2021). Oxytocin and love: Myths, metaphors and mysteries. Comprehensive psychoneuroendocrinology, 9, 100107.

Carter, C. S. (2022). Sex, love and oxytocin: Two metaphors and a molecule. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews, 143, 104948.

Earp, B. D., Wudarczyk, O. A., Foddy, B., & Savulescu, J. (2017). Addicted to love: What is love addiction and when should it be treated?. Philosophy, psychiatry, & psychology: PPP, 24(1), 77–92.

Farrelly, D., Owens, R., Elliott, H., Walden, H., & Wetherell, M. (2015). The effects of being in a “new relationship” on levels of testosterone in men. Evolutionary psychology: An international journal of evolutionary approaches to psychology and behavior, 13(1), 250–261.

Field, T. (2011). Romantic Breakups, Heartbreak and Bereavement – Romantic Breakups. Psychology, 2(4), 382–387.

Fisher, H. E., Xu, X., Aron, A., & Brown, L. L. (2016). Intense, Passionate, Romantic Love: A Natural Addiction? How the Fields That Investigate Romance and Substance Abuse Can Inform Each Other. Frontiers in psychology, 7, 687.

Gehl, K., Brassard, A., Dugal, C., Lefebvre, A. A., Daigneault, I., Francoeur, A., & Lecomte, T. (2024). Attachment and Breakup Distress: The Mediating Role of Coping Strategies. Emerging adulthood (Print), 12(1), 41–54.

Harrison, M. A., & Shortall, J. C. (2011). Women and men in love: Who really feels it and says it first? The Journal of Social Psychology, 151(6), 727–736.

Liu, N., Yang, H., Han, L., & Ma, M. (2022). Oxytocin in Women’s Health and Disease. Frontiers in endocrinology, 13, 786271.

Lewis, R. G., Florio, E., Punzo, D., & Borrelli, E. (2021). The Brain’s Reward System in Health and Disease. Advances in experimental medicine and biology, 1344, 57–69.

Marazziti, D., Dell’Osso, B., Baroni, S., Mungai, F., Catena, M., Rucci, P., Albanese, F., Giannaccini, G., Betti, L., Fabbrini, L., Italiani, P., Del Debbio, A., Lucacchini, A., & Dell’Osso, L. (2006). A relationship between oxytocin and anxiety of romantic attachment. Clinical practice and epidemiology in mental health : CP & EMH, 2, 28.

Marazziti, D., & Catena Dell’osso, M. (2008). The role of oxytocin in neuropsychiatric disorders. Current medicinal chemistry, 15(7), 698–704.

Marazziti, D., Baroni, S., Mucci, F., Piccinni, A., Moroni, I., Giannaccini, G., Carmassi, C., Massimetti, E., & Dell’Osso, L. (2019). Sex-Related Differences in Plasma Oxytocin Levels in Humans. Clinical practice and epidemiology in mental health: CP & EMH, 15, 58–63.

Melis, M. R., & Argiolas, A. (2021). Oxytocin, Erectile Function and Sexual Behavior: Last Discoveries and Possible Advances. International journal of molecular sciences, 22(19), 10376.

Neumann, I. D. (2007). Oxytocin: the neuropeptide of love reveals some of its secrets. Cell metabolism, 5(4), 231–233.

Reynaud, M., Karila, L., Blecha, L., & Benyamina, A. (2010). Is love passion an addictive disorder? The American journal of drug and alcohol abuse, 36(5), 261–267.

Riemann W. B. (2024). A qualitative analysis and evaluation of social support received after experiencing a broken marriage engagement and impacts on holistic health. Qualitative research in medicine & healthcare, 8(1), 11603.

Righetti, F., Tybur, J., Van Lange, P., Echelmeyer, L., van Esveld, S., Kroese, J., van Brecht, J., & Gangestad, S. (2020). How reproductive hormonal changes affect relationship dynamics for women and men: A 15-day diary study. Biological psychology, 149, 107784.

Scheele, D., Striepens, N., Güntürkün, O., Deutschländer, S., Maier, W., Kendrick, K. M., & Hurlemann, R. (2012). Oxytocin modulates social distance between males and females. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 32(46), 16074–16079.

Schneiderman, I., Zagoory-Sharon, O., Leckman, J. F., & Feldman, R. (2012). Oxytocin during the initial stages of romantic attachment: relations to couples’ interactive reciprocity. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 37(8), 1277–1285.

Schoenfeld, E. A., Bredow, C. A., & Huston, T. L. (2012). Do men and women show love differently in marriage? Personality & social psychology bulletin, 38(11), 1396–1409.

Seshadri, K. G. (2016). The neuroendocrinology of love. Indian journal of endocrinology and metabolism, 20(4), 558–563.

Shih, H. C., Kuo, M. E., Wu, C. W., Chao, Y. P., Huang, H. W., & Huang, C. M. (2022). The Neurobiological Basis of Love: A Meta-Analysis of Human Functional Neuroimaging Studies of Maternal and Passionate Love. Brain sciences, 12(7), 830.

Sorokowski, P., Żelaźniewicz, A., Nowak, J., Groyecka, A., Kaleta, M., Lech, W., Samorek, S., Stachowska, K., Bocian, K., Pulcer, A., Sorokowska, A., Kowal, M., & Pisanski, K. (2019). Romantic Love and Reproductive Hormones in Women. International journal of environmental research and public health, 16(21), 4224.

Wlodarski, R., & Dunbar, R. I. (2014). The Effects of Romantic Love on Mentalizing Abilities. Review of general psychology: Journal of Division 1 of the American Psychological Association, 18(4), 313–321.

Wahring, I. V., Simpson, J. A., & Van Lange, P. A. M. (2024). Romantic Relationships Matter More to Men than to Women. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 1–64.

Zou, Z., Song, H., Zhang, Y., & Zhang, X. (2016). Romantic Love vs. Drug Addiction May Inspire a New Treatment for Addiction. Frontiers in psychology, 7, 1436.

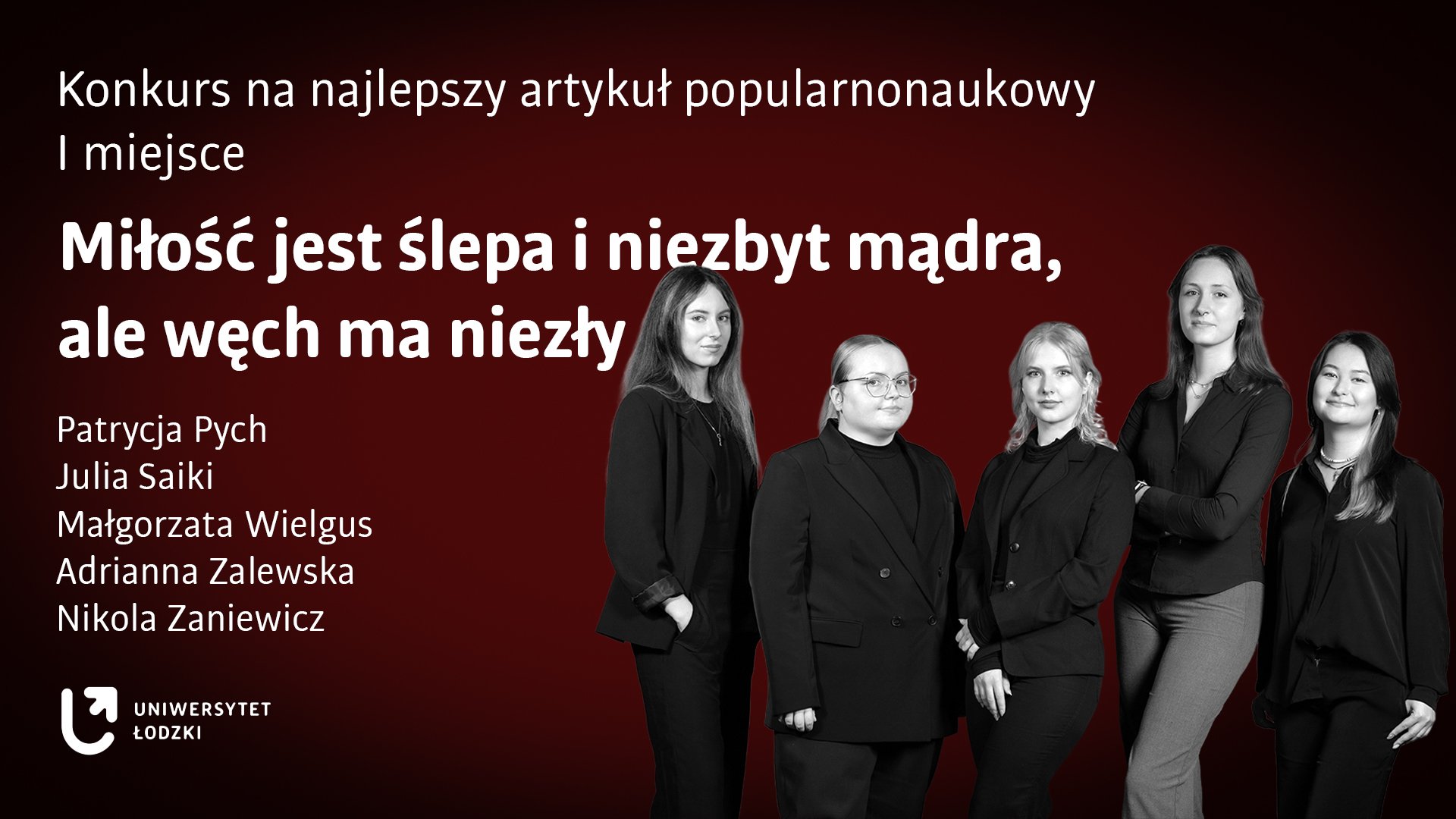

Tekst źródłowy: Patrycja Pych, Julia Saiki, Małgorzata Wielgus, Adrianna Zalewska, Nikola Zaniewicz, studentki Biologii kryminalistycznej na Wydziale Biologii i Ochrony Środowiska

Edit: Lodz University Press, Michał Gruda and Małgorzata Jasińska (Centre for External Relations and Social Responsibility of the University, University of Lodz)

Graphic design: Dr Bartosz Kałużny and Stefan Brajter (Centre for External Relations and Social Responsibility of the University, University of Lodz)