Photo of an examined human vertebra with a fracture

Photo of an examined human vertebra with a fracture

Fatigue spondylolysis – fatigue fracture of the spine

Spondylolysis is a specific fracture of the fifth lumbar vertebra. It usually results from prolonged overloading of the spine and was previously thought to be evidence of heavy, repetitive physical labour. In ancient farmers, craftsmen and logging workers, it occurred as a result of repeated bending and straightening of the back, for example, while threshing grain or processing hides. Anthropologists have compared our ancestors to modern-day Inuit or members of traditional societies, in whom similar changes are still observed.

However, new research conducted on archaeological populations from the Brześć Kujawski region suggests that this is not the whole truth.

Is it really just physical work?

It turns out that hard work wasn't the only factor contributing to this injury. Thanks to modern techniques like 3D scanning and geometric morphometric analysis of vertebral shapes, researchers have discovered that people with spondylolysis often have an anatomical predisposition to this injury.

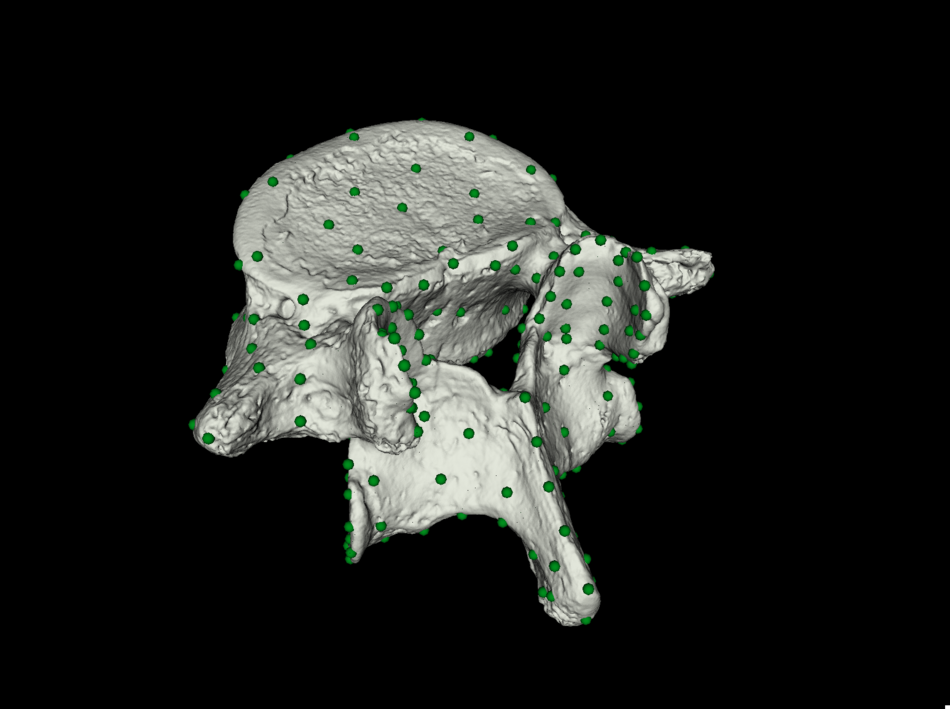

A 3D scan of a lumbar vertebra with markers (the so-called landmarks) applied to it so as to examine changes in shape

A 3D scan of a lumbar vertebra with markers (the so-called landmarks) applied to it so as to examine changes in shape

The vertebrae of individuals who suffered fractures differed from those of healthy individuals. Among other things, the following features were observed:

- a longer and lower-set spinous process, which could compress the vertebra below,

- smaller joint surfaces, which limited vertebral contact and stability,

- and a greater distance between the articular processes and the vertebral body, which increased mobility and the risk of vertebral malalignment.

In other words, the structure of some people's spines predisposed them to injury from birth. And physical labour may have been just an additional factor that accelerated the injury.

A new look at the life of ancient societies

The study results demonstrate that the current assumption that fatigue spondylolysis is simply evidence of an intense physical activity is overly simplistic. To properly interpret the bone patterns of our ancestors, we must also consider their individual anatomical characteristics.

This is important information for anthropologists who use skeletons to reconstruct the lifestyles of ancient populations. Our perception of "weary" farmers and artisans may need to be revised.

Bones – not only a testimony of death, but also of life

Research conducted on the Brześć Kujawski population demonstrates that the skeleton is not just a "remnant of a person" – it is also their biography. Every fracture, a trace of injury or a degenerative change is a record of a person's life: their work, daily activities and individual bodily limitations.

Modern techniques like geometric morphometry now allow us to "read" bones more precisely than ever before. Each new analysis allows us to peer deeper into the everyday lives of people living hundreds of years ago.

Computer-generated average shapes of vertebrae with fractures (spondylotic)

Computer-generated average shapes of vertebrae with fractures (spondylotic)

Computer-generated average shapes of vertebrae from the healthy (normal) group

Computer-generated average shapes of vertebrae from the healthy (normal) group

The research described here was conducted by Dr Joanna Mietlińska-Sauter and is being carried out as part of the project . The results of these analyses shed new light on the interpretation of spinal overload changes in ancient populations and underline the need to consider individual anatomical predispositions in paleopathological studies.

Dr Joanna Mietlińska-Sauter is a junior specialist in the Department of Anthropology at the Faculty of Biology and Environmental Protection. Her research interests focus on paleopathology and geomorphometry.

Source and photos: Dr Joanna Mietlińska-Sauter, Department of Anthropology, Faculty of Biology and Environmental Protection, University of Lodz

Edit: Kacper Szczepaniak, Promotion Centre, Faculty of Biology and Environmental Protection, University of Lodz