Andrzej Indrzejczak is a logician and philosopher working on non-classical logics and proof theory. He received his Ph.D. in 1997 and his habilitation in 2007 from the University of Lodz (Poland). Since 2015 he has been a full professor and the chair of the Department of Logic at the University of Łódź. Moreover, he is the editor-in-chief of the Bulletin of the Section of Logic, and the chairman of the editorial board of Studia Logica. He has published 8 books, including Natural Deduction, Hybrid Systems and Modal Logics (Springer 2010) and Sequents and Trees (Birkhäuser 2021), and numerous articles. Since 2008 he has organised ten editions of the conference Non-Classical Logics: Theory and Applications. Now he is the PI in the ERC project ExtenDD devoted to proof theory of definite descriptions and other complex terms and term-forming operators.

- Uniwersytet Łódzki

- ExtenDD

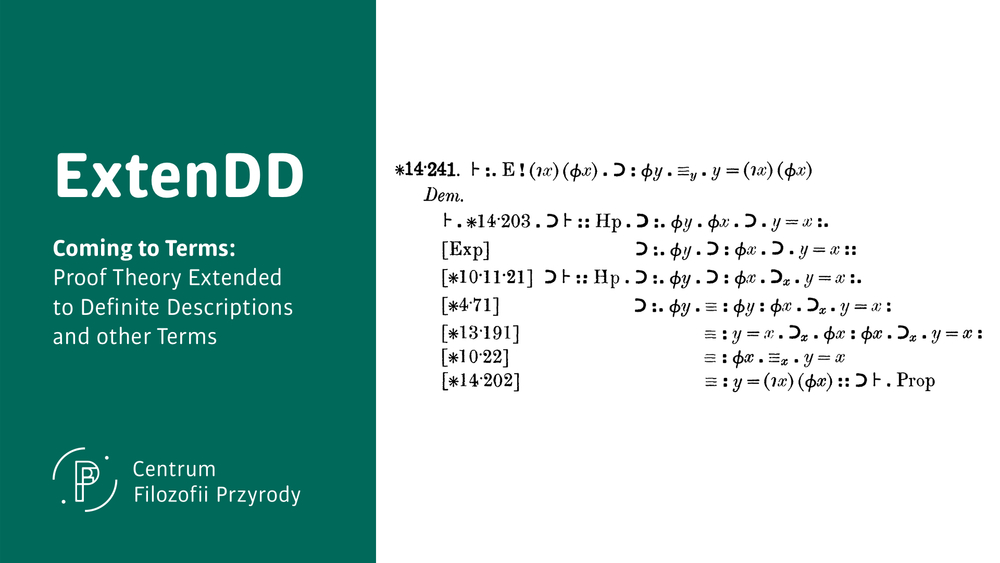

ExtenDD

Project overview

ExtenDD brings together two areas of intensive research that - surprisingly - so far have rarely come together: complex terms and proof theory. By complex terms we understand expressions that purport to denote objects like proper names, but that, unlike proper names, exhibit structure that contributes to their meaning. The most important examples of such expressions are definite descriptions. Proof theory is the mathematical study of proofs themselves. ExtenDD applies the tools of proof theory to proofs that appeal to propositions containing complex terms. A definite description is an expression of the form ‘the F’: the author of ‘On Denoting’, the author of Principia Mathematica, the present King of France. A definite descriptions aims to denote an object by virtue of a property that only it has: ‘the F’ aims to denote the sole F. The first example denotes Russell, as he was the sole author of ‘On Denoting’. Sometimes a definite description fails, because nothing or more than one thing has the property F, as in the second and third example: Principia Mathematica had two authors, Whitehead and Russell, and France is presently a republic. If a unique object has the property F, the definite description ‘the F’ is called proper; otherwise it is improper. Pride of place for the first formalisation of a theory of definite descriptions as part of a mathematical investigation belongs to Frege’s Grundgesetze der Arithmetik. But it was Russell who brought definite descriptions to prominence. Since his article ‘On Denoting’, in which Russell put forward his celebrated theory of definite descriptions, these expressions occupy a central place in philosophical research and many deep and detailed studies have been carried out in philosophical logic, epistemology, metaphysics and philosophy of language. Russell was prompted by reflections on improper definite descriptions: what do sentences like ‘The present King of France is bald’ mean? ‘The present King of France’ denotes no one, so the truth or falsity of ‘The present King of France is bald’ is not determined by whether the present King of France is bald or not. As there is no present King of France, ‘The present King of France is bald’ should not be true, as otherwise we are stating that a certain person has a certain property.

Russell accepted the principle of bivalence that every sentence is either true or false, hence the ‘The present King of France is bald’ should be false. But then it would appear that ‘The present King of France is not bald’ should be true and the same problem arises once more: if so, we are stating that a certain person fails to have a certain property. Russell concluded that sentences of the form ‘The F is G’ do not have the subject-predicate form they appear to have. According to Russell no meaning is assigned to the expression ‘the F’ standing alone, but only in the context of complete sentences in which it occurs. ‘The F is G’ means ‘There is exactly one F and it is G’. Thus the complex term ‘The F ’ disappears upon logical analysis. There are then two negations of ‘The F is G’: the external negation ‘It is not the case that the F is G’, meaning ‘It is not the case that there is exactly one F and it is G’, and the internal negation ‘The F is not G’, meaning ‘There is exactly one F and it is not G’. The former is true, the latter false. Russell’s problem is solved.

Russell’s theory of definite descriptions had enormous influence on the development of analytic philosophy in the twentieth century, as it was applied, by Russell himself and those influenced by him, to epistemology, metaphysics and philosophy of language. Scores of text books still use Russell’s theory as their official theory of definite descriptions. Despite its brilliance, Russell’s account has drawbacks. It appears to assign wrong truth values to sentences. Diogenes Laertius reports that Thales, having discovered his theorem, offered a sacrifice of oxen to the god at Delphi. According to Russell’s theory, what Diogenes reports is false, as it contains an improper definite description. That sounds wrong, if Thales did indeed offer a sacrifice at Delphi. Some philosophers, like Strawson, argued that ‘The present King of France is bald’ should be neither true nor false, as, due to the improper definite description, it is somehow defective. The second half of the 20th century saw the development of new approaches to definite descriptions. In Frege’s and Russell’s classical logic, it is assumed that every singular term denotes an object. In free logic, originating in the work of Hintikka and Lambert, this assumption is given up. Negative free logic takes a Russellian line according to which atomic formulas containing non-denoting terms are false. Neutral free logics pick up Strawson’s view that they are neither true nor false. Positive free logic permits them to be true. There is now a plethora of theories of definite descriptions, but very rarely have they been investigated from a proof theoretic perspective.

Proof Theory was founded by Hilbert at the beginning of the 20th century as the mathematical study of proofs. Initially it focused on axiomatisations of mathematical theories and proving their consistency. It was soon extended to the study of proofs outside mathematics, in particular to formal logic, which in turn was applied to the analysis of ordinary language and arguments in general. Gödel’s limitative results showed that the greatest ambition of Hilbert’s programme, to prove the consistency of arithmetic by finitary means, could not be achieved as envisaged. Gentzen’s groundbreaking work led to a substantial redefinition of the aims and tools of proof theory. It now occupies a centre stage in modern formal logic. His sequent calculus and systems of natural deduction represent the actual proofs carried out by logicians and mathematician much better than Hilbert’s axiomatic systems. These tools permit the deepest study of proofs and their properties. Following Gentzen’s work, a consensus developed over what constitutes a good proof system and the form rules of inference should take. The rules for each logical constant, expressions such as ‘not’, ‘all’ and ‘if-then’, exhibit a similar form, a remarkable systematic, as Gentzen notes. Each constant is governed by two kinds of rules for their use in proofs, and these rules govern only that constant. This form permits a precise study of where and how the logical constants are used, whether this use is essential or may be eschewed, and it is the basis for cut elimination in proofs in sequent calculus and normalisation of proofs in natural deduction. These results relate to a common phenomenon of mathematics: proofs are combined to establish new results, as lemmas are used in proofs of theorems from which corollaries are inferred in turn. Sometimes a theorem or corollary is simpler than the lemmas or theorems from which it is deduced. Gentzen’s Hauptsatz (cut elimination theorem) establishes that there is also a direct proof that proceeds from simple to complex ‘without detours’, as Gentzen says. As it is the latter in terms of which the correctness of proofs is defined, Gentzen’s result establishes that combining proofs in the said way is guaranteed to give a correct proof. In addition to these technical achievements, Gentzen’s ideas led also to the development of the more philosophically oriented proof-theoretic semantics, where the meanings of constants are defined in terms of their rules of inference.

ExtenDD will combine the paradigm of philosophy that is the theory of definite descriptions with the paradigm of proof theory that are Gentzen’s calculi. Despite the long history of research into definite descriptions, the methods developed by Gentzen have rarely been applied in research on definite descriptions. Only a small effort has so far been put into the adequate treatment of definite descriptions in this framework. The same counts for other complex singular terms such as set abstracts and number operators. ExtenDD fills this important gap in research. Applying the methods of proof theory to definite descriptions is profitable to both sides. Competing theories of definite descriptions and complex terms in general, their advantages and shortcomings, are shown in a new light. The behaviour of complex terms needs subtle syntactical analysis and requires enriching the toolkit of proof theory. ExtenDD deals with both challenges: it develops formal theories of definite descriptions and modifies the machinery of proof theory to cover new areas of application. ExtenDD will also formulate new theories of definite descriptions and other terms with an eye on proof-theoretic desiderata. ExtenDD aims to have a significant impact on proof theory, the philosophy of logic and language, linguistic, computer science and automated deduction.

Team

Nils Kürbis received his Ph.D. from King’s College London and his habilitation from the University of Bochum, where he was an Alexander von Humboldt Fellow and is an akademischer Oberrat. At the University of Lodz, besides being senior researcher in ExtenDD, he is an executive editor of the Bulletin of the Section of Logic. He’s also an honorary research fellow at University College London. His research is on proof theory and philosophical issues arising from proof theory, in particular proof theoretic semantics, where his focus was on negation, denial, falsehood and is now on proof theoretic harmony and modal operators, and definite descriptions. He has published a book Proof and Falsity. A Philosophical Investigation (Cambridge University Press 2019), edited Knowledge, Number and Reality. Encounters with the Work of Keith Hossack (Bloomsbury 2022), a Festschrift for his Doktorvater, and numerous articles on logic, philosophy of logic, philosophy of language, metaphysics and philosophical logic in ancient philosophy in leading specialist as well as generalist journals.

Yaroslav Petrukhin is a logician working on proof theory: natural deduction and sequent calculi for many-valued, modal, multilattice, and classical logics. He has written his PhD under the supervision of prof. Andrzej Indrzejczak at the University of Łódź and is currently preparing for the viva. He is now an assistant professor at the Centre for the Philosophy of Nature, University of Łódź, a position sponsored by an ExtenDD grant. Now his research is devoted to the topics of the ERC project ExtenDD: proof theory of definite descriptions and other complex terms and term-forming operators.

Michał Sochański received his Ph.D. from Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań (UAM), he also obtained M.Sc. degrees in philosophy and mathematics from the same university. In years 2019-2022 he was a post-doc in the project “Distributive Deductive Systems for Classical and Non-classical Logics. Proof theory supported with computational methods” carried out at the Departmant of Logic and Cognitive Science, UAM, where his main duties were programming and data analysis. He also worked as a data analyst / data scientist in the private sector for many years. Michał is now a research associate at the Centre for the Philosophy of Nature, University of Łódź, holding a position in the "ExtenDD" grant. His main research interests are in automated theorem proving and programming, but he also works on the philosophy of mathematics, diagrammatic reasoning, and application of combinatorics in proof theory.

Przemysław Wałęga is a senior researcher in the Department of Computer Science, University of Oxford. He obtained his Ph.D. in logic from the Institute of Philosophy at the University of Warsaw (Poland), and his B.Eng. and M.S. degrees in Mechatronics from Warsaw University of Technology, and the B.A. degree in Philosophy from the Institute of Philosophy, University of Warsaw. His research interests include knowledge representation and reasoning, reasoning about time and space, logics in AI, stream reasoning, and computational complexity. He is mainly working on computational complexity and expressive power of various logics, e.g., temporal logics, interval logics, metric logics, modal logics, description logics, and Datalog.

Michał Zawidzki is an assistant professor in the Department of Logic at the University of Lodz (Poland). He received his Ph.D. in philosophical logic from the University of Lodz in 2013. Between June 2020 and June 2023 he worked as senior research associate in AI and semantic technologies at the Department of Computer Science at Oxford University. He has been a co-organiser of several editions of the Non-Classical Logics: Theory and Applications conference. His main research interests are in non-classical (mainly modal) logics, deductive systems and automated reasoning, decidability and complexity of logical theories.

Publications

- Indrzejczak, A., Petrukhin, Y. (2023). A Uniform Formalisation of Three-Valued Logics in Bisequent Calculus. In: Pientka, B., Tinelli, C. (eds) Automated Deduction – CADE 29. CADE 2023. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 14132. Springer, Cham, 325–343. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-38499-8_19.

- Indrzejczak, A., Zawidzki, M. Definite descriptions and hybrid tense logic. Synthese 202, 98 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-023-04319-8.

- Indrzejczak, A., Kürbis, N. (2023). A Cut-Free, Sound and Complete Russellian Theory of Definite Descriptions. In: Ramanayake, R., Urban, J. (eds) Automated Reasoning with Analytic Tableaux and Related Methods. TABLEAUX 2023. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 14278. Springer, Cham, 112–130. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-43513-3_7.

- Indrzejczak, A. (2023). Towards Proof-Theoretic Formulation of the General Theory of Term-Forming Operators. In: Ramanayake, R., Urban, J. (eds) Automated Reasoning with Analytic Tableaux and Related Methods. TABLEAUX 2023. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 14278. Springer, Cham, 131–149. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-43513-3_8.

- Wałęga, P. A., Zawidzki, M. (2023). Hybrid Modal Operators for Definite Descriptions. In: Gaggl, S., Martinez, M.V., Ortiz, M. (eds), Logics in Artificial Intelligence. JELIA 2023. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 14281. Springer, Cham, 712–726. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-43619-2_48.

- Indrzejczak A., Petrukhin Y. (2024). Uniform Cut-Free Bisequent Calculifor Three-Valued Logics. Logic and Logical Philosophy 33 (2024), 463–506. https://doi.org/10.12775/LLP.2024.019.

- Kürbis, N. (2024). Normalisation for Negative Free Logics without and with Definite Descriptions. The Review of Symbolic Logic 18(1) (2025), 240–272. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1755020324000157.

- Wałęga P. A. (2024). Expressive Power of Definite Descriptions in Modal Logics. In: Marquis, P., Ortiz, M., Pagnucco, M. (eds), Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Principles of Knowledge Representation and Reasoning — Main Track. IJCAI Organization, 687–696. https://doi.org/10.24963/kr.2024/65.

- Indrzejczak A., Petrukhin Y., Bisequent Calculi for Neutral Free Logic with Definite Descriptions. In: Benzmüller C., Otten J., Ramanayake R., Proceedings of the 5th International Workshop on Automated Reasoning in Quantified Non-Classical Logics, 48–61. https://iltp.de/ARQNL-2024/CEUR/proceedings_tmp/ARQNL2024_paper5.pdf.

- Indrzejczak A., When Epsilon meets Lambda: Extended Leśniewski's Ontology. In: Benzmüller C., Otten J., Ramanayake R., Proceedings of the 5th International Workshop on Automated Reasoning in Quantified Non-Classical Logics, 62–79. https://iltp.de/ARQNL-2024/CEUR/proceedings_tmp/ARQNL2024_paper6.pdf.

- Petrukhin Y. A Binary Quantifier for Definite Descriptions in Nelsonian Free Logic. Electronic Proceedings in Theoretical Computer Science, 2024, vol. 415, pp. 5-15. https://doi.org/10.4204/EPTCS.415.5.

- Indrzejczak, A., Wałęga, P. A., Zawidzki, M. (2026). On Temporal References via Definite Descriptions in First-Order Monadic Logic of Order. In: Casini, G., Dundua, B., Kutsia, T. (eds) Logics in Artificial Intelligence. JELIA 2025. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 16094. Springer, Cham, 244–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-032-04590-4_17.

- Petrukhin, Y. (2026). On a Second-Order Version of Russellian Theory of Definite Descriptions. In: Casini, G., Dundua, B., Kutsia, T. (eds) Logics in Artificial Intelligence. JELIA 2025. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, vol. 16094. Springer, Cham, 313–326. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-032-04590-4_21.

- Kürbis, N. (2026). Definite Descriptions. In: Nesi, H., Milin, P., Fontaine, M. (eds) The Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics, 3rd Edition, Elsevier, 2026, online first, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-95504-1.00381-1.

- Kürbis, N. (ed.) (2026). Synthese Topical Collection celebrating 120 Years of Russell's `On Denoting', https://link.springer.com/collections/bcecggjfjb

Seminar

We aim to hold a seminar roughly every two weeks on Wednesdays from 12:00 to 14:00 CET during term time. It will be held online on Teams. There will be speakers from amongst the ExtenDD team as well as external speakers.

FORTHCOMING

- 4th March 2026: İskender Taşdelen (Anadolu University), Infinitary Logic Meets Russellian Definite Description Theory (abstract)

- 18th March 2026: Paul Elbourne (University of Oxford), The conjunction of predicates and modifiers in a Meaning-Dependent Grammar (abstract)

- 1st April 2026: Enamul Haque (University of Waterloo), ARM & SQLP: Introducing a New Foundation for a Path-Aware Query Language to Bridge Relational and Graph Data (abstract)

The talk will start at 13:00 CET.

PAST

- 14th January 2026: David Toman (University of Waterloo), Referring Expressions in Knowledge Representation and Information Systems (abstract)

- 7th January 2026: Lorenz Demey (KU Leuven), The Logical Geometry of Russell's Theory of Definite Descriptions (abstract)

- 3rd December 2025: Alessandro Artale, Andrea Mazzullo (Free University of Bozen-Bolzano), Decidability in First-Order Modal Logic with Non-Rigid Constants and Definite Descriptions (slides)

- 19th November 2025: Martin Giese (University of Oslo), Semantics and Reasoning for ε Terms (abstract)

- 5th November 2025: Michał Sochański, Przemysław Wałęga, Michał Zawidzki, Two types of definite descriptions in description logics (abstract)

- 22nd October 2025: Yaroslav Petrukhin, A Paradefinite Version of Russellian Theory of Definite Descriptions (slides)

- 8th October 2025: Elio La Rosa (Ludwig Maximilians Universität, Munich), Conservative Extensions of Intuitionistic Logic by Epsilon Terms over Predicate Abstraction (slides)

- 11th June 2025: Yaroslav Petrukhin, From Second-order Quantification to Second-order Definite Descriptions (slides)

- 28th May 2025: Bjørn Jespersen (Utrecht University), Vulcanology: descriptive names, invariant semantics, and dual predication (abstract)

- 14th May 2025: Michał Sochański, Michał Zawidzki, Modal Logic with Definite Descriptions, Tableaux, and Python (abstract)

- 30th April 2025: Irina Makarenko (Free University Berlin), Free Higher-Order Logic and its Automation via a Semantical Embedding (slides)

- 9th April 2025: Graham Priest (Graduate Center, City University of New York), Nothing, everything, and paraconsistent mereology (work in progress)

- 2nd April 2025: Neil Tennant (The Ohio State University), Core systems of logic with single-barreled abstraction operators (slides)

- 19th March 2025: Ed Zalta (Stanford University), Definitions in a Hyperintensional Free QML (slides)

- 5th March 2025: Ed Mares (Victoria University of Wellington), Descriptions in Informational Semantics for Relevant Logic (slides)

- 22nd January 2025: Jiří Raclavský (Masaryk University, Brno), Deduction with Non-referring Descriptions in Type-theoretic Partial Logic (abstract)

- 8th January 2025: Christoph Benzmüller (University of Bamberg / Free University of Berlin), Utilizing proof assistant systems and the LogiKEy methodology for experiments on free logic in HOL (slides)

- 18th December 2024: Elaine Pimentel (University College London), From axioms to synthetic inference rules via focusing (slides)

- 4th December 2024: Eugenio Orlandelli (University of Bologna), G3-style Sequent Calculi and Craig Interpolation Property for Logics with Russellian Definite Descriptions (slides)

- 20th November 2024: Matthieu Fontaine (University of Sevilla), Abstract Artefacts in a Modal Framework

- 6th November 2024: Nils Kürbis, Definite Descriptions in Positive Free Logic and a New Theory of Definite Descriptions based on Proof Theoretic Considerations (abstract)

- 23rd October 2024: Bartosz Wieckowski (Goethe Universität, Frankfurt am Main), Incomplete descriptions and qualified definiteness (slides)

- 9th October 2024: Andrzej Indrzejczak, Strict form of stratified set theories NF and NFU in the setting of sequent calculus (slides)

- 5th June 2024: Norbert Gratzl (Ludwig-Maximilians-University of Munich), Free Logic, Definite Descriptions, and Extensionality

- 22nd May 2024: Eugenio Orlandelli (University of Bologna), Nested sequents for quantified modal logics (slides)

- 24th April 2024: Yaroslav Petrukhin, Andrzej Indrzejczak, Bisequent Calculi for Neutral Free Logic with Definite Descriptions (slides)

- 10th April 2024: Melvin Fitting (City University of New York), First-Order Modal Logic: Predicate Abstracts and Definite Descriptions (slides)

- 20th March 2024: Andrzej Indrzejczak, When Epsilon Meets Lambda: Extended Leśniewski's Ontology (slides)

- 28th February 2024: Michał Zawidzki, Definite Descriptions in First-Order Temporal Setting (slides)

- 24th January 2024: Henrique Antunes (Universidade Federal da Bahia), Free Theories of Definite Descriptions Based on FDE (slides)

- 10th January 2024: Alessandro Artale (Free University of Bozen-Bolzano), Andrea Mazzullo (University of Trento), Temporal and Modal Free Description Logics with Definite Descriptions (slides)

- 13th December 2023: Nils Kürbis, Some Thoughts on Formalising Definite Descriptions with Binary Quantifiers in Modal Logic (slides)

- 29th November 2023: Przemysław Wałęga, Bisimulation for Propositional Modal logic with Definite Descriptions (slides)

- 15th November 2023: Andrzej Indrzejczak, Russellian Logic of Definite Descriptions and Anselm's God (slides)

- 25th October 2023: Andrzej Indrzejczak, Constructive Proof of the Craig Interpolation Theorem for Russellian Logic of Definite Descriptions (slides)

- 20th June 2023: Przemysław Wałęga, Michał Zawidzki, Andrzej Indrzejczak, Definite Descriptions in Modal and Temporal Logics (slides)

- 30th May 2023: Nils Kürbis, Normalisation for Negative Free Logics with Definite Descriptions (paper)

- 2nd May 2023: Andrzej Indrzejczak, Prospects for Classical Theory of Definite Descriptions (slides)

- 18th April 2023: Andrzej Indrzejczak, Towards a General Proof Theory of Term-Forming Operators 2 (slides)

- 4th April 2023: Nils Kürbis, A Survey of Systems Formalising Definite Descriptions by Binary Quantification (slides)

- 21st March 2023: Andrzej Indrzejczak, Towards a general proof theory of term-forming operators (slides)

First vacant slot are in Winter Term of the academic year 2025/2026, that is, on 22nd October and 5th November 2025.

If you wish to participate, please email Yaroslav Petrukhin (yaroslav.petrukhin@gmail.com) to register your interest. You will then receive a link to the Teams Meeting and regular updates on the seminar series.

If, on the other hand, you would like to give a talk in one of seminar meetings, please contact Andrzej Indrzejczak (andrzej.indrzejczak@filhist.uni.lodz.pl) to discuss the details.

Related events

Below we present a list of all events where the ExtenDD team was presenting topics related to the project.

- Nils Kürbis, Proof Theoretic Semantics for Theories of Definite Descriptions, Symposium on Proof-theoretic Semantics, 9–11 November 2022. Symposium on Proof-theoretic Semantics (google.com)

- Andrzej Indrzejczak, The coming to terms project: Extending proof theory by ?, The second Bochum–Lodz Logic Workshop, Bochum and online, Germany, 17–18 November 2022.

- Nils Kürbis, Definite descriptions via binary quantification, The second Bochum–Lodz Logic Workshop, Bochum and online, Germany, 17–18 November 2022.

- Yaroslav Petrukhin, Cut-free sequent calculi for some three-valued logics obtained via correspondence analysis, The second Bochum–Lodz Logic Workshop, Bochum and online, Germany, 17-18 November 2022.

- Andrzej Indrzejczak, Proof systems for term-forming operators: theory and application, Research Seminar hosted by Software Systems Engineering group, School of Computer Science and Engineering, University of Westminster, London, UK, 25 January 2023.

- Andrzej Indrzejczak, Michał Zawidzki, Lambda meets iota: tableaux and interpolation, FM seminar, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK, 6 February 2023.

- Andrzej Indrzejczak, Definite descriptions via term forming operators, CELL Workshop | Some Theories of Definite Descriptions from a Proof-Theoretic Perspective, London, UK, 8 February 2023.

- Nils Kürbis, Definite descriptions via binary quantification, CELL Workshop | Some Theories of Definite Descriptions from a Proof-Theoretic Perspective, London, UK, 8 February 2023.

- Andrzej Indrzejczak, Teoria dowodu dla operatorów formujących termy, Warsztaty Matematyczno-Filozoficzne, Łódź, Poland, Department of Logic, 13 March 2023.

- Andrzej Indrzejczak, Towards a General Proof Theory of Term-Forming Operators, 26th Conference Applications of Logic in Philosophy and the Foundations of Mathematics, Szklarska Poręba, Poland, 8–12 May 2023. XXVI Conference Applications of Logic in Philosophy and the Foundations of Mathematics - 27th Conference Applications of Logic in Philosophy and the Foundations of Mathematics (uni.wroc.pl)

- Nils Kürbis, Some Systems for Formalising Sentences Containing Definite Descriptions by a Binary Quantifier, 26th Conference Applications of Logic in Philosophy and the Foundations of Mathematics, Szklarska Poręba, Poland, 8–12 May 2023. XXVI Conference Applications of Logic in Philosophy and the Foundations of Mathematics - 27th Conference Applications of Logic in Philosophy and the Foundations of Mathematics (uni.wroc.pl)

- Yaroslav Petrukhin, Normalisation for Some FDE-Style Logics, 26th Conference Applications of Logic in Philosophy and the Foundations of Mathematics, Szklarska Poręba, Poland, 8–12 May 2023. XXVI Conference Applications of Logic in Philosophy and the Foundations of Mathematics - 27th Conference Applications of Logic in Philosophy and the Foundations of Mathematics (uni.wroc.pl)

- Nils Kürbis, Definite Descriptions in Modal Logic: Some Thoughts and a Proposal (inaugural lecture), Bochum, Germany. 14 June 2023. Antrittsvorlesung Prof. Dr. Kürbis (ruhr-uni-bochum.de)

- Andrzej Indrzejczak, The prospects for classical logic with definite descriptions, Colloquia. Logic and Epistemology, Bochum, Germany. 15 June 2023. Logic in Bochum - Colloquia (google.com)

- Andrzej Indrzejczak, Proof-theoretic formulation of Quinean set theory NF, Cracow Logic Conference (CLoCk) 2023, Kraków, Poland, 28–30 June 2023. Cracow Logic Conference (CLoCk) Website (uj.edu.pl)

- Yaroslav Petrukhin, Normalisation for Segerberg's natural deduction system for Boolean n-ary connectives, Cracow Logic Conference (CLoCk) 2023, Kraków, Poland, 28-30 June 2023. Cracow Logic Conference (CLoCk) Website (uj.edu.pl)

- Andrzej Indrzejczak, Yaroslav Petrukhin, A Uniform Formalisation of Three-Valued Logics in Bisequent Calculus, Automated Deduction – CADE 29, 29th International Conference on Automated Deduction. Rome, Italy, 1–4 July 2023. CADE-29 | 2023 (easyconferences.eu)

- Nils Kürbis, Some Systems for Formalising Sentences Containing Definite Descriptions by a Binary Quantifier and some Thoughts on Modal Logic, CEFISES Logic & Philosophy seminar, Louvain la Neuve, Belgium, 4 July 2023. Some Systems for Formalising Sentences Containing Definite Descriptions by a Binary Quantifier and some Thoughts on Modal Logic | UCLouvain.

- Andrzej Indrzejczak, Prezentacja wyników wypracowanych do tej pory w ramach projektu ”Coming to Terms: Proof Theory Extended to Definite Descriptions and other Terms”, Twelfth Polish Congress of Philosophy, Łódź, Poland, 11–16 September 2023. TWELFTH POLISH CONGRESS OF PHILOSOPHY (lodz.pl)

- Andrzej Indrzejczak , Michał Zawidzki, Predicate Abstracts and Definite Descriptions, Twelfth Polish Congress of Philosophy, Łódź, Poland, 11–16 September 2023. TWELFTH POLISH CONGRESS OF PHILOSOPHY (lodz.pl)

- Andrzej Indrzejczak, Yaroslav Petrukhin, A Uniform Formalisation of Three-Valued Logics in Bisequent Calculus, Twelfth Polish Congress of Philosophy, Łódź, Poland, 11–16 September 2023. TWELFTH POLISH CONGRESS OF PHILOSOPHY (lodz.pl)

- Przemysław Wałęga, Michał Zawidzki, Definite Descriptions as Modal Operators, Twelfth Polish Congress of Philosophy, Łódź, Poland, 11–16 September 2023. TWELFTH POLISH CONGRESS OF PHILOSOPHY (lodz.pl)

- Nils Kürbis, A Theory of Definite Descriptions. Part I: Background.Motivation. Proof-Theory, Twelfth Polish Congress of Philosophy, Łódź, Poland, 11–16 September 2023. TWELFTH POLISH CONGRESS OF PHILOSOPHY (lodz.pl)

- Nils Kürbis, A Theory of Definite Descriptions. Part II: Iota Terms and Binary Quantifiers. Semantics. Some Thoughts on Modal Logic, Twelfth Polish Congress of Philosophy, Łódź, Poland, 11–16 September 2023. TWELFTH POLISH CONGRESS OF PHILOSOPHY (lodz.pl)

- Yaroslav Petrukhin, Normalisation for Segerberg's natural deduction system for Boolean n-ary connectives, Twelfth Polish Congress of Philosophy, Łódź, Poland, 11-16 September 2023. TWELFTH POLISH CONGRESS OF PHILOSOPHY (lodz.pl)

- Andrzej Indrzejczak, Nils Kürbis, A cut-free, sound and complete Russellian theory of definite descriptions, 32nd International Conference on Automated Reasoning with Analytic Tableaux and Related Methods, TABLEAUX 2023, Prague, Czech Republic, September 18–21, 2023. TABLEAUX 2023 | 32nd International Conference on Automated Reasoning with Analytic Tableaux and Related Methods (tableaux-ar.org)

- Andrzej Indrzejczak, Towards Proof-Theoretic Formulation of the General Theory of Term-Forming Operators, 32nd International Conference on Automated Reasoning with Analytic Tableaux and Related Methods, TABLEAUX 2023, Prague, Czech Republic, September 18–21, 2023. TABLEAUX 2023 | 32nd International Conference on Automated Reasoning with Analytic Tableaux and Related Methods (tableaux-ar.org)

- Przemysław Wałęga, Michał Zawidzki, Hybrid Modal Operators for Definite Descriptions, 18th Edition of the European Conference on Logics in Artificial Intelligence, JELIA 2023, Dresden, Germany, 20–22 September 2023. JELIA 2023 (tu-dresden.de)

- Nils Kürbis, Deductive Semantics, Seminar of the University of Stirling, 28 September 2023.

- Yaroslav Petrukhin, Definite descriptions in Nelson's logics, Trends in Logic XXIII. Bridges between Logic, Ethics and Social Sciences (BLESS). 70 years of STUDIA LOGICA, Toruń, Poland, 22–25 November 2023. BLESS (umk.pl)

- Andrzej Indrzejczak, Anselm’s God and theories of definite descriptions, Trends in Logic XXIII. Bridges between Logic, Ethics and Social Sciences (BLESS). 70 years of STUDIA LOGICA, Toruń, Poland, 22–25 November 2023. BLESS (umk.pl)

- Andrzej Indrzejczak, Prezentacja badań Katedry Logiki i projektu ExtenDD, World Logic Day(s) in Poland 2024, Łódź, Poland, 15 January 2024. WLD2024 (google.com)

- Nils Kürbis, Definite Descriptions. Russell and Beyond, World Logic Day(s) in Poland 2024, Łódź, Poland, 15 January 2024.WLD2024 (google.com)

- Yaroslav Petrukhin, The Recent Advances in Natural Deduction for Many-Valued Logic, World Logic Day(s) in Poland 2024, Łódź, Poland, 15 January 2024. WLD2024 (google.com)

- Andrzej Indrzejczak, Leśniewski's Ontology Satisfies Interpolation, The Sixth Asian Workshop on Philosophical Logic (AWPL2024), Sapporo, Japan, 4–6 March 2024. AWPL 2024 - Program (google.com)

- Yaroslav Petrukhin, Definite Descriptions in Nelson's Logic (Online), The Sixth Asian Workshop on Philosophical Logic (AWPL2024), Sapporo, Japan, 4–6 March 2024. AWPL 2024 - Program (google.com)

- Andrzej Indrzejczak, Hybrid Logic Extended with Lambda and Iota Operators, Sapporo One-day Workshop on Hybrid Logic and Proof Theory, Sapporo, Japan, 7 March 2024. Sapporo Workshop 2024 Spring (google.com)

- Nils Kürbis, A Theory of Definite Descriptions Formalised by Binary Quantification for Modal Logic, Sapporo One-day Workshop on Hybrid Logic and Proof Theory, Sapporo, Japan, 7 March 2024. Sapporo Workshop 2024 Spring (google.com)

- Andrzej Indrzejczak, Application of Bisequent Calculus to Neutral Free Logic with Definite Descriptions (A joint work with Yaroslav Petrukhin), LLAL@GSIS (II), Sendai, Japan, 9 March 2024. LLAL@GSIS - LLAL@GSIS (2) (google.com)

- Nils Kürbis, Some Systems for Formalising Definite Descriptions with a Binary Quantifier in Free Logic, LLAL@GSIS (II), Sendai, Japan, 9 March 2024. LLAL@GSIS - LLAL@GSIS (2) (google.com)

- Andrzej Indrzejczak, When Epsilon meets Lambda; Extended Leśniewski's Ontology, A Workshop on Russell, Leśniewski and beyond, Tokyo, Japan, 13 March 2024. Home (google.com)

- Nils Kürbis, Definite Descriptions formalised by Binary Quantifiers, A Workshop on Russell, Leśniewski and beyond, Tokyo, Japan, 13 March 2024. Home (google.com)

- Nils Kürbis, A Theory of Definite Descriptions Formalised by Binary Quantification for Modal Logic, Seminar at Stirling, 9 April 2024.

- Andrzej Indrzejczak, Yaroslav Petrukhin, Bisequent Calculi for Neutral Free Logic with Definite Descriptions, 27th Conference Applications of Logic in Philosophy and the Foundations of Mathematics, Szklarska Poręba, 6–10 May 2024. Program - 27th Conference Applications of Logic in Philosophy and the Foundations of Mathematics (uni.wroc.pl)

- Andrzej Indrzejczak, When Epsilon Meets Lambda: Extended Leśniewski's Ontology, 27th Conference Applications of Logic in Philosophy and the Foundations of Mathematics, Szklarska Poręba, 6–10 May 2024. Program - 27th Conference Applications of Logic in Philosophy and the Foundations of Mathematics (uni.wroc.pl)

- Przemysław Wałęga, Referring to Modal Worlds via Definite Descriptions, 27th Conference Applications of Logic in Philosophy and the Foundations of Mathematics, Szklarska Poręba, 6–10 May 2024. Program - 27th Conference Applications of Logic in Philosophy and the Foundations of Mathematics (uni.wroc.pl)

- Andrzej Indrzejczak, Russell, Definite Descriptions and Anselm’s God: Approaches to Concepts, Formal Methods and Science in Philosophy V, Dubrovnik, Croatia, 16–18 May 2024. Inter University Centre Dubrovnik (iuc.hr)

- Andrzej Indrzejczak, Yaroslav Petrukhin, Bisequent Calculi of Definite Descriptions in Neutral Free Logic, Formal Methods and Science in Philosophy V, Dubrovnik, Croatia, 16–18 May 2024. Inter University Centre Dubrovnik (iuc.hr)

- Andrzej Indrzejczak, Proof Systems for Hybrid Logic with Lambda and Iota Operators, Czech Gathering of Logicians 2024 and Kurt Gödel Day 2024, Brno, the Czech Republic, 27–28 May 2024. Czech Gathering of Logicians 2024 and Kurt Gödel Day 2024 [27 - 28 May 2024] Brno, the Czech Republic] (muni.cz)

- Yaroslav Petrukhin, Natural deduction for definite descriptions in strong Kleene free logic, Cracow Logic Conference feat. Trends in Logic 2024, Kraków, Poland, 18–21 June 2024. Cracow Logic Conference feat. Trends in Logic - 2024 (uj.edu.pl)

- Andrzej Indrzejczak, Do theories of definite descriptions support Anselm's God?, Logic Colloquium 2024, Gothenburg, Sweden, 24–28 June 2024 https://lc2024.se/talks/

- Yaroslav Petrukhin, Natural deduction for neutral free logic with definite descriptions, Logic Colloquium 2024, Gothenburg, Sweden, 24–28 June 2024 https://lc2024.se/talks/

- Andrzej Indrzejczak, Yaroslav Petrukhin, Bisequent Calculi for Neutral Free Logic with Definite Descriptions, ARQNL 2024 Automated Reasoning in Quantified Non-Classical Logics 5th International Workshop (associated with IJCAR 2024), Nancy, France, 1 July 2024. ARQNL 2024 - Programme (iltp.de)

- Andrzej Indrzejczak, When Epsilon meets Lambda: Extended Leśniewski's Ontology. ARQNL 2024 Automated Reasoning in Quantified Non-Classical Logics 5th International Workshop (associated with IJCAR 2024), Nancy, France, 1 July 2024. ARQNL 2024 - Programme (iltp.de)

- Andrzej Indrzejczak, Proof Theory extended to definite description & other terms, Proof Representations: From Theory to Applications, Dagstuhl Seminar 24341, Dagstuhl, Germany, 18–23 August 2024. https://www.dagstuhl.de/seminars/seminar-calendar/seminar-details/24341

- Nils Kürbis, Normalisation for Negative Free Logic with Definite Descriptions, NCL'24: Non-Classical Logics. Theory and Applications 2024, Łódź, Poland, 5–8 September 2024. https://easychair.org/smart-program/NCL'24/program.html

- Nils Kürbis, A Theory of Definite Descriptions, NCL'24: Non-Classical Logics. Theory and Applications 2024, Łódź, Poland, 5–8 September 2024. https://easychair.org/smart-program/NCL'24/program.html

- Andrzej Indrzejczak, Sequent Calculi for Logics of Classes, NCL'24: Non-Classical Logics. Theory and Applications 2024, Łódź, Poland, 5–8 September 2024. https://easychair.org/smart-program/NCL'24/program.html

- Przemysław Wałęga, Michał Zawidzki, Modal logic with definite descriptions: complexity, bisimulation, and tableaux, NCL'24: Non-Classical Logics. Theory and Applications 2024, Łódź, Poland, 5–8 September 2024. https://easychair.org/smart-program/NCL'24/program.html

- Yaroslav Petrukhin, Andrzej Indrzejczak, Bisequent Calculi for Neutral Free Logic with Definite Descriptions, NCL'24: Non-Classical Logics. Theory and Applications 2024, Łódź, Poland, 5–8 September 2024. https://easychair.org/smart-program/NCL'24/program.html

- Yaroslav Petrukhin, A Binary Quantifier for Definite Descriptions in Nelsonian Free Logic, NCL'24: Non-Classical Logics. Theory and Applications 2024, Łódź, Poland, 5–8 September 2024. https://easychair.org/smart-program/NCL'24/program.html

- Nils Kürbis, A Theory of Definite Descriptions for Modal Logic, XXVI Deutscher Kongress für Philosophie, Sektion Logik und Philosophie der Mathematik, Münster, Germany, 22–26 September 2024. https://www.uni-muenster.de/DKPhil2024/programm/sektionen.html

- Przemysław Wałęga, Expressive Power of Definite Descriptions in Modal Logics, KR 2024: 21st International Conference on Principles of Knowledge Representation and Reasoning, Hanoi, Vietnam, 2–8 November 2024. https://kr.org/KR2024/schedule.php

- Andrzej Indrzejczak, Proof Systems for Extensions of Hybrid Logic with Complex Terms, seminar of the Institute of Cybernetics of the Estonian Academy of Sciences, Tallin, Estonia, 10 January 2025.

- Andrzej Indrzejczak, Bisequent Calculus and its Applications to Non-Classical Logics, World Logic Day 2025 in Tallin, Estonia, 11 January 2025. https://cs.ioc.ee/lsg/wld25/

- Michał Zawidzki, Modal logic with definite description operators (in Polish), World Logic Day 2025 in Łódź, Poland, 15 January 2025. https://www.filozofia.uni.lodz.pl/aktualnosci/szczegoly/program-swiatowego-dnia-logiki-w-lodzi-2025

- Yaroslav Petrukhin, Essence and accident modalities meet Belnapian truth values, World Logic Day 2025 in Łódź, Poland, 15 January 2025. https://www.filozofia.uni.lodz.pl/aktualnosci/szczegoly/program-swiatowego-dnia-logiki-w-lodzi-2025

- Nils Kürbis, 120 Years of On Denoting, World Logic Day 2025 in Łódź, Poland, 15 January 2025. https://www.filozofia.uni.lodz.pl/aktualnosci/szczegoly/program-swiatowego-dnia-logiki-w-lodzi-2025

- Yaroslav Petrukhin, Second-order Definite Descriptions, Zagreb Logic Conference 2025, Zagreb, Croatia, 14–17 February 2025. https://sites.google.com/view/zlc25/

- Nils Kürbis, A Puzzle about Harmony and the Rules for Definite Descriptions, Bochum Logic and Epistemology Colloquium, Bochum, Germany, 24 April 2025. https://sites.google.com/view/logic-in-bochum/colloquium

- Szymon Chlebowski, Yaroslav Petrukhin, Fregean Definite Descriptions in Non-Fregean Logic, 28th Conference Applications of Logic in Philosophy and the Foundations of Mathematics, Szklarska Poręba, Poland, 5–9 May 2025. https://www.applications-of-logic.uni.wroc.pl/History/XXVIII-Conference-Applications-of-Logic-in-Philosophy-and-the-Foundations-of-Mathematics

- Yaroslav Petrukhin, Fregean Hypersequent Many-Valued Versions of Essence and Accident Modalities in FDE-Based Logics, 28th Conference Applications of Logic in Philosophy and the Foundations of Mathematics, Szklarska Poręba, Poland, 5–9 May 2025. https://www.applications-of-logic.uni.wroc.pl/History/XXVIII-Conference-Applications-of-Logic-in-Philosophy-and-the-Foundations-of-Mathematics

- Nils Kürbis, 120 Years of Russell’s ‘On Denoting', 28th Conference Applications of Logic in Philosophy and the Foundations of Mathematics, Szklarska Poręba, Poland, 5–9 May 2025. https://www.applications-of-logic.uni.wroc.pl/History/XXVIII-Conference-Applications-of-Logic-in-Philosophy-and-the-Foundations-of-Mathematics

- Andrzej Indrzejczak, Constructive Neologicism in the Theory of Classes, 28th Conference Applications of Logic in Philosophy and the Foundations of Mathematics, Szklarska Poręba, Poland, 5–9 May 2025. https://www.applications-of-logic.uni.wroc.pl/History/XXVIII-Conference-Applications-of-Logic-in-Philosophy-and-the-Foundations-of-Mathematics

- Michał Sochański, Michał Zawidzki, Modal Logic with Definite Descriptions, Tableaux, and Python, 28th Conference Applications of Logic in Philosophy and the Foundations of Mathematics, Szklarska Poręba, Poland, 5–9 May 2025. https://www.applications-of-logic.uni.wroc.pl/History/XXVIII-Conference-Applications-of-Logic-in-Philosophy-and-the-Foundations-of-Mathematics

- Przemysław Wałęga, Graph Neural Networks, Modal Logics, and Definite Descriptions, 28th Conference Applications of Logic in Philosophy and the Foundations of Mathematics, Szklarska Poręba, Poland, 5–9 May 2025. https://www.applications-of-logic.uni.wroc.pl/History/XXVIII-Conference-Applications-of-Logic-in-Philosophy-and-the-Foundations-of-Mathematics

- Andrzej Indrzejczak, How much of Set Theory can we derive from Logic?, special session at the workshop: Proof Representations: From Theory to Applications, Banff International Research Station, Canada, 1–6 June 2025. https://www.birs.ca/events/2025/5-day-workshops/25w5406

- Nils Kürbis, A Theory of Definite Descriptions for Modal Logic, Saul Kripke Center, New York, US, 11 June 2025. https://kripkecenter.commons.gc.cuny.edu/2025/05/08/summer-logic-double-feature/

- Nils Kürbis, Tennant on Deduction, Definite Descriptions and other Term Forming operators, conference Logic, Inference and Rationality. A Conference in Honour of Neil Tennant, Ohio State University, Columbus, US, 13–14 June 2025. https://sites.google.com/view/tennantfest

- Nils Kürbis, Tennant on Deduction, A Puzzle about Harmony and the Rules for Definite Descriptions, Carl Friedrich von Weizäcker Kolloquium, University of Tübingen, Germany, 25 June 2025. https://uni-tuebingen.de/forschung/zentren-und-institute/carl-friedrich-von-weizsaecker-zentrum/news-und-events/carl-friedrich-von-weizsaecker-kolloquium/

- Yaroslav Petrukhin, On a Second-order Generalisation of Russellian Theory of Definite Descriptions, Cracow Logic Conference (CLoCk) 2025, Kraków, Poland, 26–27 June 2025. https://iphils.uj.edu.pl/clock/2025/

- Yaroslav Petrukhin, From second-order quantification to second-order definite descriptions, Logic Colloquium 2025, Vienna, Austria, 7–11 July 2025 https://www.colloquium.co/lc2025

- Nils Kürbis, 120 Years of Russell’s 'On Denoting’, Logic Colloquium 2025, Vienna, Austria, 7–11 July 2025. https://www.colloquium.co/lc2025

- Andrzej Indrzejczak, Proof theoretic study of negative free logics with definite descriptions, Logic Colloquium 2025, Vienna, Austria, 7–11 July 2025. https://www.colloquium.co/lc2025

- Nils Kürbis, Russell, On Denoting and Definite Descriptions formalised via Binary Quantification, Center for Mathematical Philosophy, University of Munich, Germany, 24 July 2025. https://www.mcmp.philosophie.uni-muenchen.de/events_this-_week/kuerbis_20250724/index.html

- Andrzej Indrzejczak, Cut Elimination for Negative Free Logics with Definite Descriptions, CADE-30: 30th International Conference on Automated Deduction, Stuttgart, Germany, 28 July–2 August, 2025. https://www.dhbw-stuttgart.de/cade-30/program/

- Yaroslav Petrukhin, On a Second-Order Version of Russellian Theory of Definite Descriptions, JELIA 2025: 19th edition of the European Conference on Logics in Artificial Intelligence. Kutaisi, Georgia, 1–4 September 2025. https://easychair.org/smart-program/JELIA2025/

- Andrzej Indrzejczak, Przemysław Wałęga, Michał Zawidzki, On Temporal References via Definite Descriptions in First-Order Monadic Logic of Order, JELIA 2025: 19th edition of the European Conference on Logics in Artificial Intelligence, Kutaisi, Georgia, 1–4 September 2025. https://easychair.org/smart-program/JELIA2025/

- Michał Sochański, Przemysław Wałęga, Michał Zawidzki, Two Types of Definite Descriptions: Theory and Implementation, DL 2025: 38th International Workshop on Description Logics, Opole, Poland, 3–6 September 2025. https://dl25.cs.uni.opole.pl/schedule/

- Andrzej Indrzejczak, How much set theory is in logic? On some applications of proof theory in the logic of classes (in Polish: Ile teorii mnogości zawiera logika? O pewnych zastosowaniach teorii dowodu w logice klas), invited talk, 10th Forum of Polish Mathematicians, Białystok, Poland, 8–12 September, 2025. https://10fmp.uwb.edu.pl/program.php

- Yaroslav Petrukhin, From second-order quantification to second-order definite descriptions, Polish Congress of Logic, 22–26 September 2025, Toruń, Poland. https://logika.net.pl/language/en/pcl-2/program/

- Nils Kürbis, Formal Theories of Definite Descriptions. Part I, Polish Congress of Logic, 22–26 September 2025, Toruń, Poland. https://logika.net.pl/language/en/pcl-2/program/

- Nils Kürbis, Definite Descriptions in Free Core Logic, Polish Congress of Logic, 22–26 September 2025, Toruń, Poland. https://logika.net.pl/language/en/pcl-2/program/

- Szymon Chlebowski, Yaroslav Petrukhin, Fregean Definite Descriptions in Non-Fregean Logic, Polish Congress of Logic, 3rd Workshop on Non-Fregean Logics, 22–26 September 2025, Toruń, Poland. https://logika.net.pl/language/en/pcl-2/program/

- Andrzej Indrzejczak, Ontology of Leśniewski in the Proof-Theoretic Setting, invited talk, Polish Congress of Logic, 22–26 September 2025, Toruń, Poland. https://logika.net.pl/language/en/pcl-2/program/

- Andrzej Indrzejczak, Formal Theories of Definite Descriptions. Part III, Polish Congress of Logic, 22–26 September 2025, Toruń, Poland. https://logika.net.pl/language/en/pcl-2/program/

- Michał Zawidzki, Formal Theories of Definite Descriptions. Part II, Polish Congress of Logic, 22–26 September 2025, Toruń, Poland. https://logika.net.pl/language/en/pcl-2/program/

- Nils Kürbis, Definite Descriptions in Free Core Logic, 6th Taiwan Philosophical Logic Conference, National Taiwan University, Taipei, Taiwan, 23–25 October 2025. https://sites.google.com/view/tplc-2025/

Funded by the European Union (ERC, ExtenDD, project number: 101054714). Views and opinions expressed are however those of the team members only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Council. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.